Home » Posts tagged 'Academic life'

Tag Archives: Academic life

Talk: Games for Academic Life

Prof Anna L Cox gives keynote speech “Games for

Academic Life” at GALA 2020, Games and Learning Alliance conference.

A copy of the slides is available for download.

Academic Life in 2019

Today many of my colleagues are on strike. I’m not joining them today because I am on leave to attend the funeral of a university friend who died a few weeks ago in his mid-40s.

His sudden and unexpected death has shaken me. It’s frightened me more than other events this year – two of my fittest and healthiest friends had heart attacks. If these things can happen to them, they can happen to me. It has made me want to refocus my life and think harder about what is important. I don’t want to have regrets.

I spend most of my life at either 100 miles an hour or so exhausted that I can’t move – I literally had no option but to spend 2 hours yesterday napping on the sofa. I was completely shattered. This kind of life isn’t good for my mental or physical health. It’s not how I want to live. It makes me scared that I’ll be the next person in my friendship group to have a major health problem. And that will have serious consequences for my family.

Despite the fact that I’m on leave today, I have spent the morning doing work activities. The lines between work and non-work are very blurred. It’s really effortful to create and maintain the boundaries between them when there is so much to do.

Academic life is engaging and exciting and full of responsibility. I need to ensure my taught students get a good experience, can pass their assessments and receive useful feedback so they can improve their learning. I have PhD students to train and support as they learn to deal with the frequent rejections that come from reviewers. I have grants to write so that my post-docs have jobs – without funding they will be made redundant. I have made a commitment to try to make my institution a better place for everyone to work in my role as Vice Dean Equality, Diversity and Inclusion. And I have promised to help those in my academic community by reviewing papers and organising conferences and to foster links between universities and schools by being a school governor. All of these activities give me a sense of reward and accomplishment. I’ve made all these commitments because I think they’re important and want to keep them. In addition there are frequent requests for reference letters to support people getting new jobs or going for promotion. And from members of the media who want comments which could help the public understand and engage with science. And other things that I can’t even remember right now.

No wonder I am exhausted.

But I’m not alone. This week Mary Beard tweeted…..

“Can I ask academics of any level of seniority how many hours a week they reckon they work. My current estimate is over 100. I am a mug. But what is the norm in real life. ?” https://twitter.com/wmarybeard/status/1198351088832962560

Responses seem to fall into a few categories:

· Accusing her of lying: People find it hard to believe that can be telling the truth – who can work that number of hours?

· Shaming her for having privilege: People accusing her of perpetuating a culture of overwork and unnecessarily increasing the competitive culture within academia

· Sympathy and acceptance: People who recognise that they’re in a very similar position

UCL’s standard working week is 36.5 hours excluding meal breaks. Two of my colleagues shared the outcome of their attempts to track how many hours they’ve worked this year. By the end of August they had already worked their full annual allocation of hours. They work around 55hrs per week on average. So September to December they will work for free. Not standard weeks but still averaging around 55hrs per week. By the end of the year they will have worked an extra 50% above their contracted hours. I think this is common. It’s very difficult to say no to the endless requests or to deal with the guilt of letting someone down. Instead we put our own mental and physical health at risk, we do the work of 1.5 people, and our employers continue to take advantage of us.

Last year, in 2018, I went on strike along with many of my colleagues. As a result I lost a substantial amount of pay. Whilst this meant that some of lectures were cancelled and students were impacted, the reality is that I worked throughout the strike period. I worked a standard week as well as spending time on the picket line and on a march.

Some will say that my actions undermined the strike action by minimising it’s impact. But my actions were necessary to support my own mental health. I couldn’t deal with the stress of a huge pile of work that would all have to be done in the weeks after the strike. The reality of academia is that if you are away on leave for any reason, no one covers your job for you. You just have to work harder and longer afterwards.

During this strike period I don’t have any teaching duties. Even if i did, going on strike seems like an ineffective form of protest – it might hurt our students in the short term but it leaves untouched those who have the authority to improve the situation for all university staff. I’m not sure whether I’m going to strike in the coming days. This is certainly a time for reflection about what matters.

Sabbatical thoughts on productivity, the planning fallacy and recovery – month 2 of the commitment calendar

Following my previous post on the commitment calendar I was asked to share the spreadsheet that I am using to help me get a sense of what I have committed to do each month. The link to that is here.

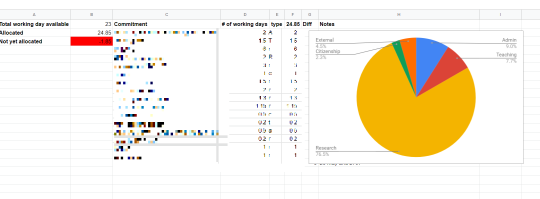

This is now the second month of using it. I sat down on the morning of the first working day of the month to plan out what I was going to get done, and when that was going to happen. I have found it easiest to use half days as the smallest unit. Coming up with the list of stuff that has to be included takes a few steps:

1) Standard predictable things like scheduling some time each week to review my to-do list, plan what needs to be done, update this spreadsheet, schedule stuff in my calendar, etc. I’m scheduling half a day a week for this. The first one of these in the month is used for planning the rest of the month but it’s not clear what the rest of these slots will be used for yet. Sure, I’ll need a bit of time every week to check my to-do list etc but I hope I won’t need half a day a week. This will allow for a little slack in the schedule. I am also being explicit that I need time to do email. I am blocking out half a day a week to get my inbox to zero and respond to messages and do small admin tasks.

2) Then there is the stuff that will vary depending on what your roles are as an academic. I’m including supervision time: how much time you devote to this will depend on how many students you have but need to cover all the time spent on face to face contact, reading and commenting on drafts, etc. I’ve also added in time for teaching (to cover preparation, contact time and marking) and time for citizenship/admin roles such as sitting on committees and leading programmes.

3) Stuff that’s happening this month only – this will be things like attending a conference or taking some holiday.

The next thing that happened was I realised just how over-committed I was for the month. As a result I decided that there were some things that weren’t going to happen this month. Having to make hard decisions and accepting that I can’t get everything done that I might like to has made it easier to say no to other requests that have come in over the past week.

I have found it useful to schedule half day slots in my diary that relate directly to the commitments so i know when I am going to get each of these things done. This is helping me see what can get done in half a day (and what can’t!). For example, is half a day enough time to read a paper and write a review for it? I am hoping that this provides me with more insight into how long it takes you to do different things so it is easier to plan with more accuracy (though it’s well known that we find it very difficult to avoid being overconfident about what we can achieve in a given time https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planning_fallacy ) Even engaging in this planning task has helped me realise that there are some things that I can’t do as early as I would like.

So far this week my 3 working days have been MUCH longer than I had wanted or planned for them to be. This suggests that I’m still overestimating what can be done in a given amount of time. It has also meant that today (Thursday) I’ve been much less productive than I wanted to be and have struggled to motivate myself to do the things I had planned to do. Hopefully tomorrow I will have recovered enough to have the energy to catch up with the things on today’s list that haven’t been finished.

Reflections on a writing retreat

One of the to-dos on my sabbatical bucket list is to submit a particular grant proposal I have been slowly working on with two colleagues. We all work at different institutions and it seemed like a great idea to find an opportunity to get our ideas down on paper – preferably whilst we were co-located and away from our usual places of work.

Earlier this year I discovered that Maureen Michael from Room For Writing was leading a writing retreat to be held in May. I asked my two colleagues if they would be interested in going. I thought the structure provided by the retreat would give us the best chance of getting it done as we would be forced not to spend the whole day talking! A few weeks later we were all booked to go.

We scheduled a skype call a couple of weeks ahead of the retreat to refresh our memories and make sure that we still agreed on what we wanted to do. Our planning included breaking down the writing of the proposal into discrete chunks and scheduling them each for a particular time slot.

The day of the retreat arrived. Two of us arrived in Glasgow early and spent the morning talking about the ideas we had for the project.

By lunchtime the three of us were together and some more chat ensued. At 3pm we were met by a taxi and 3 other retreaters for the journey to the Black Bull Hotel in Gartmore, about an hour outside of Glasgow.

After tea and coffee, and introductions, twelve people sat down to start a 5 minute free writing task in which we had to write in full sentences (but without editing) and answer 2 questions: for the writing task we were going to focus on, what had we already written for it and what did we want to achieve by the end of day 3, the end of day 2, and the end of the coming 60 minute session?

We then formed pairs and talked for 5 minutes each about what we were going to write. We were instructed to ask questions to help the other person to articulate a very clear goal. Sixty minutes later we had completed our first writing slot and we had written three work-packages. We were rewarded with a fantastic three course dinner.

The Black Bull Hotel in Gartmore is a really charming place, with humorous staff and an amazing cook. Breakfast consisted of fruit, cereal, porridge, and everything you would expect from a full Scottish breakfast. Elevenses were freshly baked scones or gorgeous fluffy pancakes served with jam, cream and maple syrup. Lunch on day 2 was salad and jacket potatoes with tuna and prawns. And on day 3 was fajitas and salad and quiche. There was also afternoon tea on all three days that included things like this delicious and beautiful “cake object”.

The retreat was structured to include 8 writing sessions that each lasted 60-90 minutes. The morning and afternoon breaks lasted 30 minutes and lunchtime was 90 minutes that included strong encouragement to take a walk or go for a run.

Over the course of the three days we completed 10.5 hours of focused writing, went on 5 walks, and were very well looked after. I have come away from this experience feeling incredibly productive (and consequently a bit tired!) but also cared for, and reminded of a slower way of working. Maureen is very skilled at creating an atmosphere in which being focused and productive feels easy. She also carefully guides you through re-evaluating your goals so that, at the end of the process, you focus on your successes and achievements and have insight into how to set realistic goals for writing.

So how did it go? We we wrote a grant proposal! We have about 9000 new words that have been revised by each of us several times so they’re of reasonably high quality. To be completely honest we have achieved more than I had dared to believe was possible in the time.

We used the breaks to relax but also to chat about progress and to share ideas about how to develop the ideas in our proposal. That meant that, compared to other participants at the retreat, we probably “worked” through the breaks rather than using them entirely for recovery.

That said, the process didn’t feel frantic or like we were under pressure but felt relaxed and was quite unlike my usual working days. I don’t usually take breaks when I’m working and sometime even miss out on lunch. I know it’s not good for me but somewhere between being immersed in my work and under pressure to get lots of things done it’s been an easy habit to develop. I’m going to try to change that and see if I can schedule substantial breaks in my day. I’m interested to see how that impacts my work and wellbeing (though perhaps I will eat less cake than when in Gartmore!).

If you’re interested to know more about structured writing retreats like the one I attended then you can read Rowena Murray & Mary Newton’s paper here.

You can find more information about Room For Writing on their website.

Creating my commitment calendar & getting to grips with the to-do list

I’m forever on the lookout for ways to help me better manage my to-do list. I hate the feeling of being behind and constantly missing deadlines. As I’m currently on a 3 month sabbatical and now that my responsibilities for CHI2019 are over now seems like a good time to review what i do and try to improve things for the future.

I was recently reminded of Amy Ko’s blogpost in which she describes keeping a “commitment calendar” that covers each month into the next 2 years. I remember when i first heard her talk about it on Geraldine Fitzpatrick’s podcast and wondering how on earth she managed it – it seemed like a difficult thing to do. I just couldn’t work out how you would know what you were going to be doing that far ahead. But something made me think that this might be worth trying to i sat down with my notebook and devoted 2 pages to mapping out the next 2 years.

It was actually much easier than i expected it to be. I tend to take holiday with predictable regularity dictated by school holidays – so that was the first thing i put in. And then the conferences that i usually attend also tend to follow a predictable pattern so I added those. I could then predict when i would most likely be working on the papers for those conferences, when i would have teaching and marking to do, and when my PhD students would need feedback on their upgrade reports and final thesis drafts. I’ve also got a bunch of other things already in my calendar – talks i’ve committed to giving, workshops I’m planning on attending, etc.

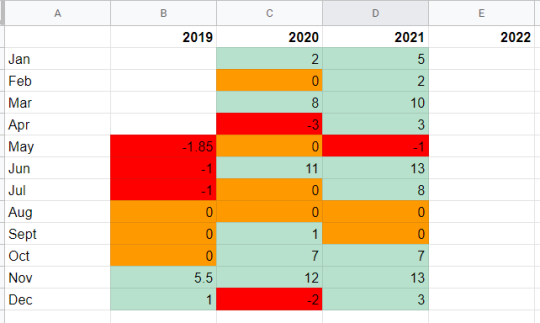

What was immediately visible was that I already know things that I’m going to be doing in 2 years time and which month those commitments are going to fall in. I could also see that the next 6 months look really busy! But just how busy?

I set about counting how many working days there were in each month and adding this information to the calendar. And then i started estimating how many days each commitment was going to take up. Now it was really clear that I have over-committed myself!

And then i remembered another thing I needed to add into this month! It was clear that paper commitment calendar just wasn’t going to cut-it. As more and more things that I have committed to come to mind I was going to very quickly run out of space on the sheets in my notebook. So I set about transferring it all into a spreadsheet.

And because I love a good pie chart I also worked out what percentage of my time I was spending on research, teaching, institutional citizenship (service) and external/knowledge exchange.

Next I created an overview sheet…..

…and had it automatically colour code each month as red if I am over-committed, amber if I have no capacity to take on any more, and green if there are work days still available to get work done. I was surprised to find that the month I got to the CHI conference is routinely full, as is December.

Engaging in this exercise has given me a whole new perspective on my workload. It now seems really obvious why I struggle to get things done and always feel like I’m behind. If I hadn’t done this I would have thought that October 2019 was pretty empty and that I could easily say yes to a whole host of new things. Now, when I receive a request to do something (examine a thesis, review a paper, join in on a grant with a short deadline, etc) I check the spreadsheet and actually think about how much work will be involved, and whether or not i have time to do it. If I have got time then I add it to the spreadsheet. If I haven’t, I say no. Given that i have so few “spare” days left this calendar year, I’m going to be very picky about what I say yes to using them for.

Edit: following a few requests i made a copy of my spreadsheet available if you want to try it out. Copy and paste it and then you can edit it and put in your own stuff. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1jzfJP17AboKEKcqM9if-2fPobnHnD3bvl6E96cd95P4/edit?usp=sharing

Leadership: the importance of talking about failure

Reblogged from https://martaelizabethcecchinato.wordpress.com/2016/06/20/leadership-the-importance-of-talking-about-failure/

There was a CV going around social media and the press posted by a tired academic who wanted to expose just how much our culture is based on success and competition. It was eye opening… As a fairly young academic myself, it was encouraging to read and know that others have bad days too. About a month ago, I was talking to a colleague I look up to and found out that behind her successes there were rejected papers. I had no idea. In academia, it is common to celebrate successes, and perhaps brag about them too, but it is also common to complain about reviewer 2, the biased editor, or the tardiness with which a paper is handled. There’s a good summary of typical academics and how to handle them here. Being a woman in STEM it can be considered even more important to just show off the best results and just how successful one is, to compete against gender bias. So when I attended the event “Women in Leadership” organised by UCL PALS Athena Swan I was expecting an empowering talk on how to stand up against men and show off our best traits. I have never been so wrong.

The talk was given by Harriet Minter, founder and editor of the Guardian column ‘Women in Leadership’. She started off by telling her story of how she became a leader, which was not only filled with all the ingredients of a woman in the workplace – self-doubt, wanting to fix everything, imposter syndrome – but covered also a good handful of failures and knock downs. More importantly, for every failure or road bump, she presented a series of lessons learnt, showing off what a great leader she is.

There were other two refreshing elements in her talk: 1.First of all, most of the talks or articles for women in the workplace, focus on the idea that we need to learn to say ‘no’ in order to set boundaries, protect our time, and prevent us from our worst enemy: “the red cross nurse syndrome” (that’s what we call in Italian the tendency that women have to fix everything and take care of others in spite of their own health). Harriet instead reminded us that ‘no’ is not always the answer, and that new opportunities, exciting projects, and adventures only come if you don’t say ‘no’ all the time, but remember to say ‘yes’. 2.Secondly, although the title of the event was “Women in Leadership” and she referred to several role models throughout, the lessons are for everyone. I counted three men in the packed room of about 50 people, which is the highest male attendance I’ve ever seen at such events. More than focusing on empowering women alone, her talk was aimed at changing the overall mentality of women in the workplace, and therefore aiming to both men and women.

So what were some of the lessons learnt?

PROCEED UNTIL APPREHENDED

No matter the amount of failure, you can only succeed if you don’t give up. So whenever you are stuck, have a problem, or have an idea you don’t know how to concretise: 1.Scale it down. Starting off with a grand project can be frightening for you, or even those that are supposed to invest in you. By scaling it down, you have an achievable starting point to build on. 2.Find an ally, to be reassured and have a boost in confidence, especially when things get hard. 3.Just start. Although this sounds a lot like the best marketing slogan, she and Nike have a point: start small and simple. Things will never change unless you do something about it.

WE ARE ALL HEROS WITH A QUEST

She then compared her story with that of any hero’s narrative. Whenever you watch a Disney or Marvel movie, or any other film/book/comic that has a hero, there are always five elements of the story. Filmmakers, theatre producers, and storytellers study this at school, like my friend Elisa who had first pointed out these five elements to me six years ago, but we just tend to think that they belong to the fictional life, while instead this happens to all of us: 1.There is a hero with a quest and a bunch of skills in a backpack. 2.The hero starts his/her journey so excited and filled with hope, that he/she suddenly missed the bit pothole in front of him/her, and falls down. 3.While the hero is stuck down there, in order to get back on track to his quest, he/she reaches in the backpack. While the skills he/she finds in there are not necessarily the right ones to get him/her out, it’s how he/she uses them that will get him/her out [*will get back to this point later] 4.As the hero climbs out of the pothole, a mystery stranger arrives and puts him/her back on the path 5.The hero finally succeeds in his/her quest.

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN ENDURANCE AND RESILIENCE

This is the point of the story where the best advice she was ever given, Proceed until apprehended, ties in with the hero’s narrative. When the hero is in the pothole, he/she can keep trying, keep going, just like a runner can reach the finish line if he/she pursues long enough. But when they get out, they might not have any energy left to notice the stranger or proceed on the path. This is where resilience comes in. Resilience is the ability to still stand and walk away when you reach the finish line, or you climb out of the dungeon and proceed on your path to success. Even if we don’t have the right skills for the task, it’s up to us to adapt the skills that we do have, to make things work for us. By learning from past failures and falls, we can practice and learn our resilience skills.

FIND YOUR TEAM

Finally, the last bit of advice comes from her encounter with Sheryl Sandberg, who performed the equivalent productivity sprint of a month’s work in just three hours, whilst visiting The Guardian. If behind every successful man they say there is a strong woman, behind every successful woman there is a team. In Sheryl’s case, it was made up of people who would help her keep to time and take care of menial tasks. In our case, this team is our support network that can help us in rough times, and on whom we can rely on for the skills we lack. We just have to remember to play in other people’s teams too…

Going back to the beginning of this post, the importance of talking about failure lies in the ability to roll up your sleeves, stand up again and learn from it. In my giant OneNote notebook called unimaginatively ‘PhD’, I now have a section called “failures”, where I write all the things that go wrong and what I can learn from them, as well as keep track of my own hero journey.

Sabbatical week 1: decisions decisions

I’m on sabbatical for the next term. Many academics take this opportunity to relocate to another university, often one in another country, for a change of scenery and an opportunity to recharge their batteries. This isn’t something that’s open to me given that I have two young children and a partner with a fulltime job that doesn’t provide the same opportunity for a paid sabbatical. As a result, I have a term without teaching and (most of my) admin duties. It seems challenging to make the most of this opportunity so that I look back on this time and feel that it was really different in some way from any other term. Given that a change is as good as a rest, how am I going to change things without changing things in my personal life too much?

In order to help me decide what to do I talked to some friends and colleagues and also posted the question on facebook. I got a bunch of interesting suggestions: https://www.facebook.com/Anna.L.Cox/posts/10151893679466189

So what did I settle on?

- Blogging (suggested by Charlene Jennett) – hence this post. I’m going to write something every week.

- I have some short trips planned to give some talks

- Maria Kutar suggested life-logging, which given my current interest in personal informatics tools, is also something i’m going to add to my list.

- Paul Marshal’s suggestion of juggling might morph into ‘juggling work-life balance in new ways’, probably not quite what he had in mind, but I’m going to try out a few things, including Steve Payne’s suggestion of time off from facebook and email!,

- Jo Iacovides suggested playing video games.

- And Lisa Tweedie and Ann Blandford suggested voluntary work

Best get busy then!

The true course of scientific research

Brian Romans’ blogpost that he wrote in response to that of Chris Chambers discusses the frequent reality of the course of scientific research. It’s perhaps even an understatement to say that things don’t always work out quite the way you expect them to. Brian argues that there’s a lot to be learned from a piece of research that ‘fails’ and that “stumbling about” can sometimes mean that you stumble into something significant. As Daniel Richardson’s rather honest account makes clear, this way of talking about the process of research is in stark contrast to the way we teach it:

“It generally begins at a conference bar or through an email with a friend when we’ll come up with a half-formed idea and we won’t have any idea what we’re doing. We’ll plunge through the literature, we’ll revise, we’ll completely change the focus, or do one experiment that won’t work but then something strange will happen and we’ll investigate that instead. It’s a collaborative, shoddy, directionless sort of exploration, completely different from the very clean, straightforward way that we teach research.”

It’s not just that we teach research as though it were a very linear process, but it’s also the way we usually report it in papers, theses, talks etc. I remember being a grad student and wondering how on earth I was ever going to create a thesis that hung together, out of a patchwork of studies with unpredicted results. More recently, it felt rather unnatural at first to describe a “failed” experiment in my talk last week at CHI2012. On the one hand it didn’t contribute anything to the theory being put forward in the paper, but, on the other, it was important to demonstrate how our original ideas (about how challenge leads to increased experience of immersion in videogames) were just wrong.

Having spent a few moments myself in a conference bar last week, I’m full of enthusiasm and half-formed ideas, which I hope to investigate over the coming months. Rather than being daunted though about whether experimental results will work out as I expect them to, I’m already looking forward to the unpredictable journey ahead and the challenge of weaving together an interesting story out of whatever happens….perhaps even in time for the CHI2013 deadline.